Martin Jan Månsson

Martin Jan Månsson is an urban planner and map maker with a special interest in the global interconnectedness of places. His work involves creating historical travel and trade route maps spanning medieval and early modern times. In this blog post, he reflects upon lessons learnt while compiling a comprehensive map covering the global 19th century, with the aid of hundreds of English travel journals and texts. The 19th century was a pivotal era for cities and ports worldwide, and it was the beginning of a globe-spanning standardization process that continues to nibble away on local flavor to this day.

In many ways, the 19th-century city represents an adolescent stage for numerous modern urban areas, growing out of their constraining city walls, exploring partnerships beyond their immediate surroundings and asserting their individuality by carving out specialized niches that would fit in a globe-spanning production chain. The later 20th- and 21st-century city in turn is a grown up version of this. They all seem to have gone through university, fathered several suburbs and entered the figurative rat race that is the service economy. The grown up modern city may struggle to find convincing selling points that sets it apart from its peers. To resolve this, it may yet have the luxury of looking back to its adolescent stage and showcase its past individuality, the wild stories of long-gone memories and the back-in-fashion wardrobe of clothing that is its architectural heritage.

The 19th century is a particularly convenient era to bring forth owing to its simultaneously familiar yet unthinkable ways of living. A relatable yet novel world. The globe-trotting traveler of the 1800s might have felt a similar level of paradoxical familiarity when visiting the wide array of homegrown customs and flavors of places outside of his home region. One unknown 19th-century English traveler in the melting pot of Singapore made a special case for the distinctiveness of customs when he wrote that:

“Arabs, Jews, Malays, Chinese, Indians and Europeans thrive here, but they all retain their home traditions. The Chinese let his hair grow, the Arab fashions his turban and the Englishman drinks his porter.” (Vidal et al. 1850)

This writer was not alone in making sure to write about the look and feel of a place or its people. Regardless if the same Englishman had visited Scotland, Italy, Brazil or China, every visit to a new place would be an occasion for an anthropological contribution.

These cultural distinctions were not just reserved for the typical hairstyle or habits of people, but also applied to the vessels they used to reach ports like Singapore. The Arab-Indian Dhow vessels with their well-tested triangular sail patterns lay in port next to the gigantic junk-rigged Chinese ships. From the eastern spice islands came large Pencalang Bugis ships with giant rectangular tilted sails. From Europe and America, the various kinds of square-rigged ships were latecomers to the scene but represent the finishing touch to this diverse ensemble of long-voyage vessels.

While all of these vessels were capable of long voyages, it was only the Americo-European ships that regularly left the Asian waters for more distant ports. This western design dominated the movement of bulky goods across the world, and soon enough also shove aside competing native designs in the regional Indian ocean trade. After this century, such a diverse array of ship designs would never again amass in one place.

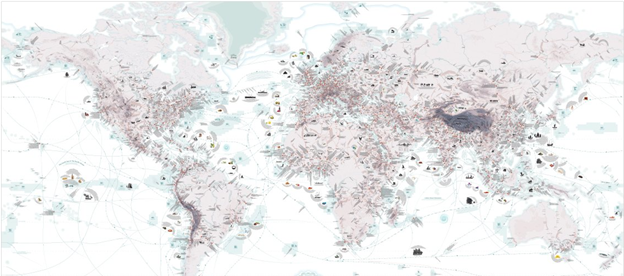

The past unique attributes of different cultures and places, as just outlined in the case of Singapore, is but one of a thousand stories that my custom-made World Atlas of 19th Century Trade and Travel tells. The map itself is a compilation of tales as told by contemporaries; important to notice however is that they are relayed by mostly European, Russian and American captains and travelers. Singapore is but one of over 3000 featured places, most of which with descriptions of local curiosities and their role in the larger interconnected trade system at the time.

Like the four ship types presented earlier, the Atlas also provides visual examples of an additional 170 different modes of transportation across the world. The very network on which these vehicles traveled is in turn made tangible with over 1500 illustrated travel times, allowing one to calculate the immense undertakings of past travelers. For example, a trip from London to Mexico City would involve an initial 50-60 days of sailing to Havana. From there one would embark on a steamboat to Veracruz for 3-4 days. The final stretch between Veracruz to Mexico City would then be a matter of 20 days worth of mule riding.

The people who undertook such long trips were merchants, industrialists, captains, sailors, lucky-seekers, gold diggers, military personnel and aspiring settlers. This diverse group of people had never in history had such an expedient and safe road ahead of them. Fewer ships at the time felt the need to equip themselves with cannons, and piracy was essentially eradicated save for some holdouts in East Asia. The globe was more connected than ever, but the long travel times were still a preserving factor for homegrown traditions.

These long travel times that one had to endure would always involve multiple changes of transportation modes and a daily adventure to find a place for sleeping. And behind every good nights’ sleep and vehicular change was a town or city responsible for providing such services. Naturally, all such towns were not equals: some had more strategic locations than others in relation to both regional and global networks.

Mountain passes, river navigability, railway infrastructure, water depth, network centrality and resource extraction are just some of the determining factors for the importance of locations - all featured in the Atlas. A brief overview of the internal logic of China’s logistically strategic points sheds light on the reason behind the existence of some of its cities. Each black location on the Chinese map represents a transition from one mode of travel to another. For each change of mode, a large and busy transhipment industry and corresponding culture was readily in place.

Many of these cities are still notable in China’s economy today, and anyone traveling on the ground would still pass by these same locations. But few would still see the necessity for a frequent change of vehicle type or longer stay-overs. Such a raison d’être of cities has faded, and yet another layer of unique qualities setting it apart from its peers has been peeled off.

Another notable fascination of the 19th century globetrotters was to take special notice of the produce of a place; possibly in an effort to report back to their employer or the public about business opportunities. In these kinds of reports, a special phrase is often repeated among several different contemporaries, namely ‘finest quality’ - used as an epithet to a wide array of goods such as an extra sweet variety of oranges or an especially compliant breed of camels. Well over 300 of these ‘finest quality’ products, and where to find them, are recorded in the Atlas.

While high-profile multinational brands may be the image carriers of quality products today, the places from where the products were gained was seemingly more important to writers in the 19th century. An example of this can be found in the rather simple commodity of ice, or frozen water. In the mid-1800s, ice was traded globally from colder regions to warmer areas of the world in order to cool drinks or to allow for the making of ice cream. The first ice that was traded in this fashion had its origins in Lake Wenham near Salem, Massachusetts. This ice was apparently so well regarded that some Norwegian ice traders claimed that their ice was from the same lake (Weightman 2003).

While much more can be said about the kind of information included in this mapping project, it is ultimately a description of a past time when places were distinct, yet fully interconnected. My hope is that this Atlas can function as a collective memory, describing why our cities are where they are and how they played an integral part in the historical world machine. But importantly, it is also a celebration not just of places, but of the networks that tied them all together. From matchstick-themed infrastructure in the small town of Jönköping to the gliding leisure shows in the global city of Doha, cities across the world tap into their history in order to increase local identity and global relevance - but how can we make visible the lost web of routes that allowed our cities to become so special in the first place?

Acknowledgement

Martin Jan Månsson is an urban planner, spatial analyst and map maker interested in the interconnectedness of places and movement of goods throughout history.

This blog has been written in the context of discussions in the LDE PortCityFutures research community. It reflects the evolving thoughts of the author and expresses the discussions between researchers on the socio-economic, spatial and cultural questions surrounding port city relationships. This blog was edited by the PortCityFutures editorial team: Wenjun Feng, Vincent Baptist and Foteini Tsigoni.

Selection of Relevant References

Balfour, E. Cyclopedia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia (Madras: Scottish, Lawrence and Foster, 1873)

Baur, C.F. Atlas für Handel und Industrie (Mannheim: Friedrich Bassermann, 1857)

Vidal, Cpt. A. T. E., et al. The Nautical Magazine for 1850 (London: Simkin, Marshall and Co., 1850)

Weightman, G. The Frozen Water Trade: A True Story (New York: Harper Collins, 2004)

Wells Williams, S. The Middle Kingdom (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1900)