Martin Valinger Sluga and Lucija Ažman Momirski

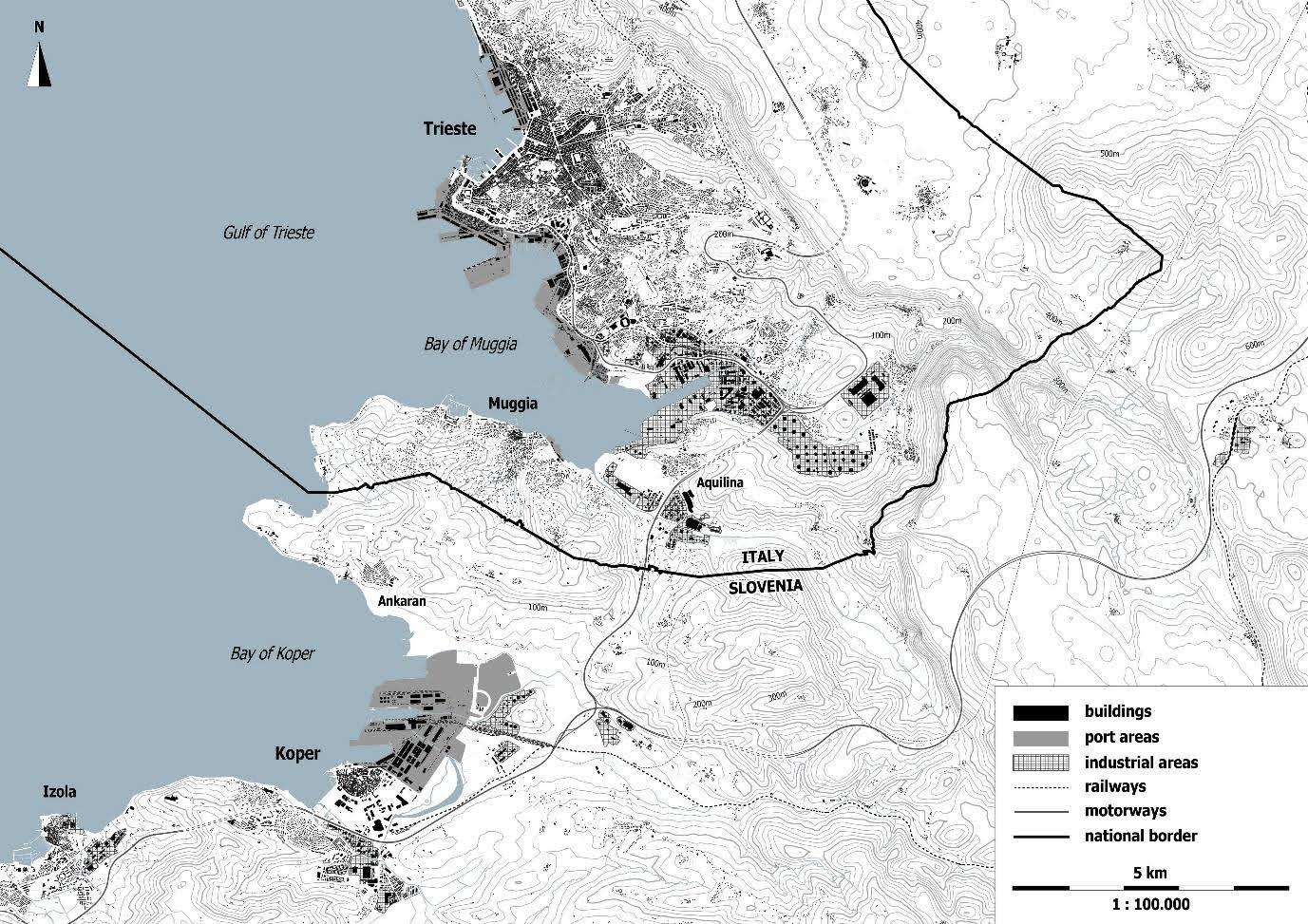

Ports and port cities in proximity represent particularly interesting case studies in planning theory and practice. Their spatial planning is often intricately related due to their geographical and other types of proximities (e.g. institutional). However, they can also diverge significantly due to unique local and regional circumstances. In this blog, Martin Valinger and Lucija Ažman summarise the key findings of their article recently published in Planning Perspectives. The article examines how geographical proximity, dynamic geopolitical circumstances, and a unique border context have shaped the development trajectories of the neighbouring ports of Koper (Slovenia) and Trieste (Italy), located in the northeastern Adriatic. The blog adds to the article as it explores new insights into the current status quo, where various local civil groups on both sides of the border are becoming increasingly involved in port planning discussions.

In planning literature, little attention has been given to how geographical proximity affects the planning strategies of neighbouring ports. Significant research gaps also remain for the northern Adriatic, a complex region marked by numerous border shifts. These shifts led to a convergence of shared identities, transformed customs, as well as conflicting symbols—such as monuments, public commemorations, and architectural styles—that influenced the appearance of the local (urban) environments (Klabjan, 2019). Against the theoretical background of ports in proximity, Mellinato (2022) notes that the case of the northern Adriatic has unique characteristics and can introduce a new path for historical research on adjacent ports within the same gateway region but operating under different political systems.

The historical development of Koper and Trieste has been shaped by both competition and cooperation under various ruling entities. Despite being only a few kilometres apart, they have rarely developed in parallel. This has led to somewhat idiosyncratic conditions, as the permeability and rigidity of the border did not always affect the relatedness of planning efforts.

Historical Context and Geopolitical Shifts

By the early 19th century, when the Austrian Empire united both port cities under one single rule, Koper had already lost its regional importance as the main salt-trading port. Meanwhile, Trieste thrived and established itself as a major European port by the beginning of the 20th century. After the First World War, both cities became part of Italy and Trieste’s port was reduced to a peripheral role within the Italian port system. One of the most critical geopolitical issues in early post-World War II Europe was the border between former Yugoslavia and Italy. To reduce military tensions in disputed border areas, the UN Security Council established the Free Territory of Trieste (FTT) in 1947, dividing it into Zone A (including Trieste) and Zone B (including Koper). In 1954, the cities were redivided: Italy annexed the former and Yugoslavia the latter. The main objective of the Western Allies through such an agreement was not to control the city of Trieste, but its port, protecting the transport routes between the Adriatic Sea and Central Europe (Griesser-Pečar, 2007).

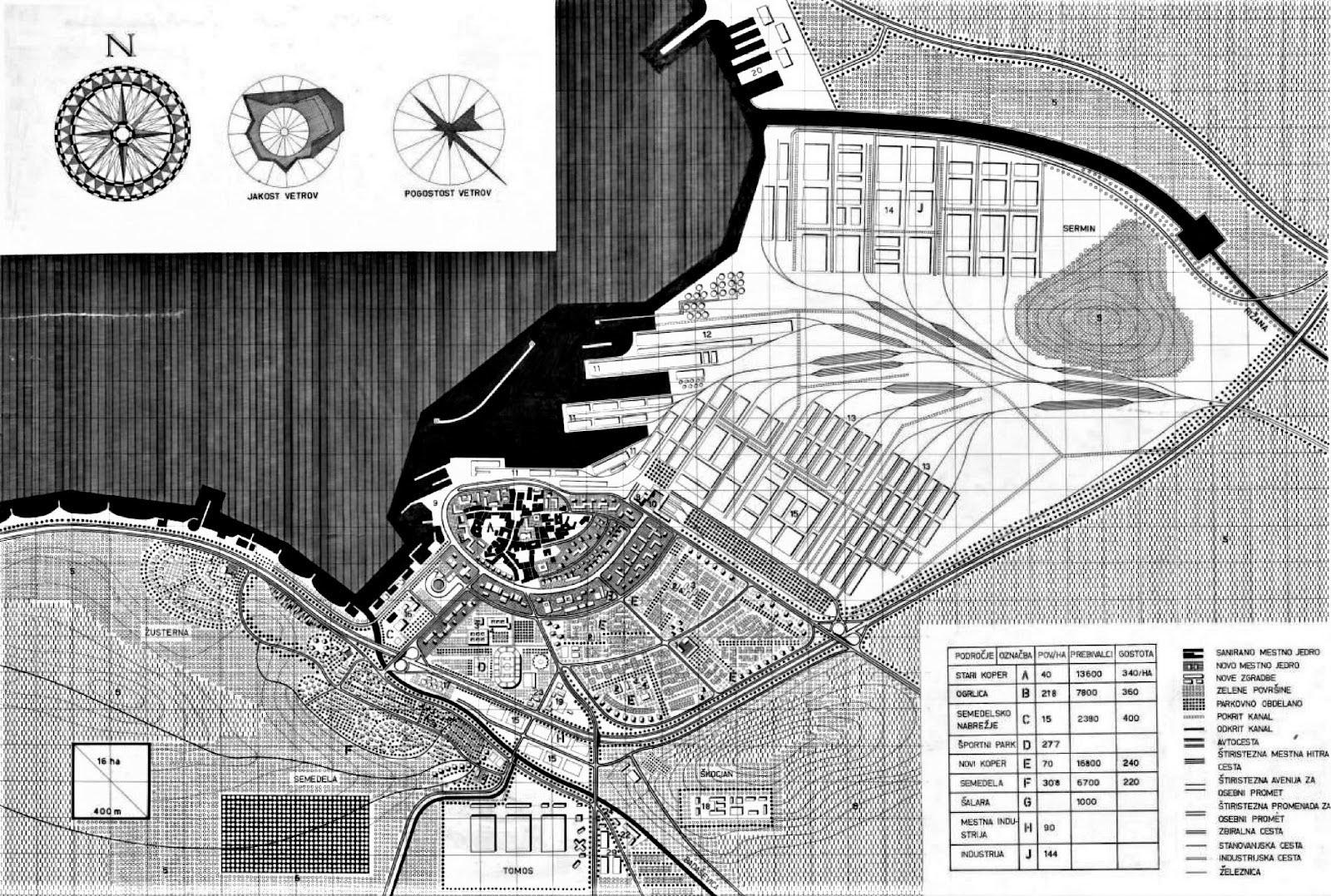

The newly established national border led to significant socio-economic, political, and spatial disintegration of the region (Panjek, 2007). Despite its important geostrategic role “at the edge of the West,” Trieste became geographically isolated and lost its traditional hinterland, being squeezed in between the border and the sea. The new territorial arrangement granted Slovenia, the most economically developed Yugoslav republic, access to international waters. With Trieste removed as its historic economic and cultural centre, Koper emerged as the region’s largest and strategically most important city, where a new port would be constructed from scratch, starting in 1957.

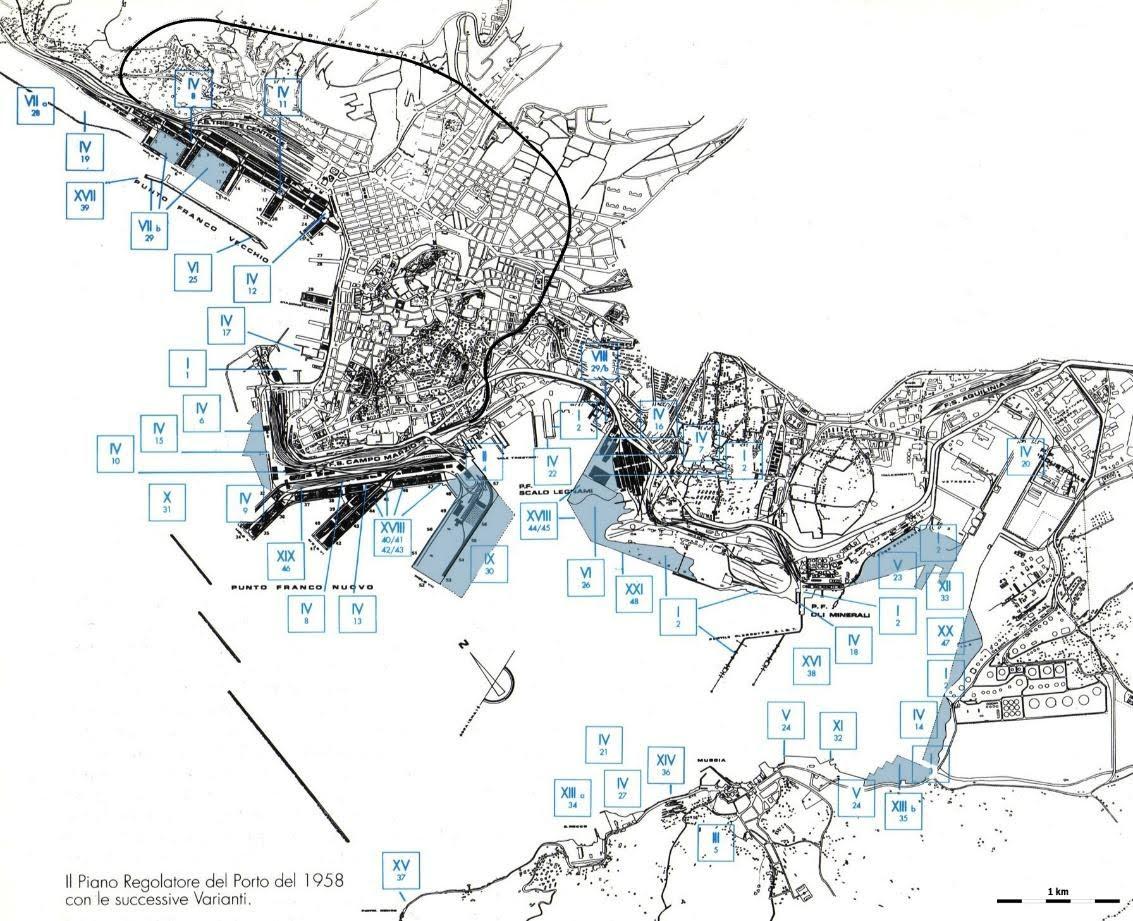

During the late 1950s and 1960s, both ports developed independently, although the newly constructed Port of Koper was influenced to some extent by the layout of the New Port of Trieste. By the 1970s, the Yugoslav–Italian border became the most permeable border between any capitalist and communist state in Europe (Repe, 1998). While attempts for closer port cooperation and economic rehabilitation never managed to gain ground, increased cross-border exchange has led to a certain degree of complementarity due to cargo specialisation: the port of Trieste mainly handled liquid cargo, while the port of Koper specialised in dry bulk cargo.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Trieste’s geostrategic role changed significantly once again. The city took on the role of a “gateway city” and an important “bridge to the East” (ESDP, 1999). This shift also became a priority in planning, as Trieste’s potential as a pivotal port and logistical hub in an expanding Europe was to be promoted (Bialasiewicz and Minca, 2010). As the now independent Slovenia drew closer to the European Union (EU), political and economic optimism grew on both sides of the border. When the Port of Koper acquired a thirty-year concession for a container terminal in the port of Trieste, it seemed as though both ports would eventually merge into a single port system (Trupac, 2003). Persistent phantom borders (e.g. historical borders that have lost their relevance due to changing (geo)-political conditions but later reappeared in public discussions and symbolic actions) have prevented closer interrelatedness in the ports’ operation and planning.

Contemporary Challenges in Port Cooperation

The historical development of these two ports differ significantly, but their histories are nonetheless interwoven and marked by complex political, economic, social, and cultural relations. Both port authorities have shown remarkable resilience and adaptability to recurring new conditions. Transforming from contested regions into thriving gateways required nuanced planning strategies, allowing them to maintain distinct identities and unique development paths, all the while closely monitoring one another.

Today, both ports are members of the North Adriatic Ports Association (NAPA) which promotes the northern Adriatic route as an efficient and environmentally friendly alternative to northern European ports. However, operational cooperation to avoid bottlenecks, improve rail interoperability, bridge missing transport links, and especially improve cross-border connections remains weak, and strategic, commercial, and infrastructural cooperation is practically non-existent. Therefore, any prospects for complimentary or even coordinated planning—for example, in terms of a joint port masterplan or planning joint hinterland connections—remain dim.

Port Planning and Public Participation

Port masterplans’ approval, implementation, and revision procedures are often too complex, time-consuming, and rigid. Moreover, there is a noticeable lack of public participation regardless of local stakeholders’ desire to voice their opinions on future port planning prospects. Recently, different Adriatic port cities have experienced renewed local engagement amid growing regional port competition that drives further port expansions. These new civil groups are getting increasingly involved in the port planning and port-related urban regeneration discussions, advocating for more collaborative planning efforts.

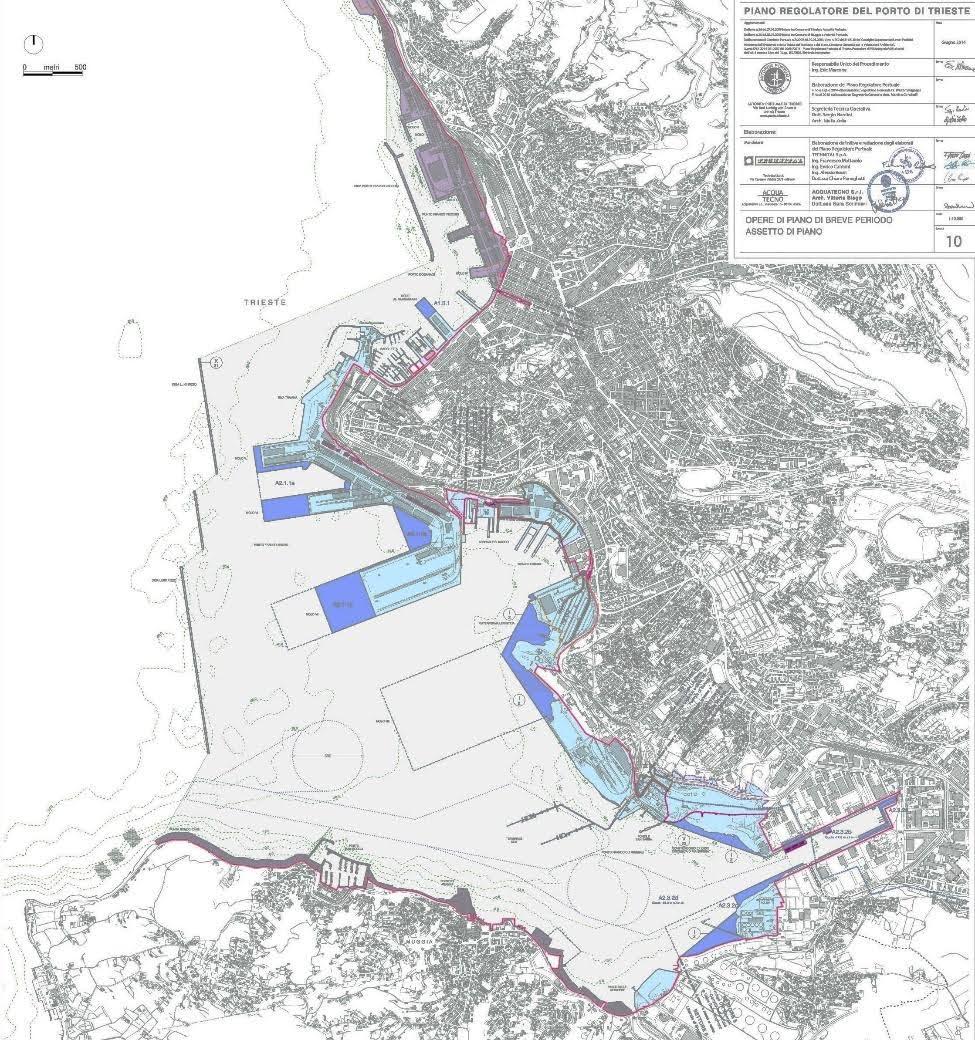

In Trieste, the Regulatory Plan for the Port of Trieste (PRP) outlines the port’s long-term spatial and functional vision, including key infrastructural developments to boost future throughput. The plan serves as a tool for developing and regenerating the wider port area, encompassing adjacent industrial areas, logistics facilities, and municipalities. For example, it provides the general framework for the municipality-led transformation of the abandoned Porto Vecchio (the Old Port) into “Porto Vivo” (the Living Port). The project has faced strong opposition from some scholars, experts, NGOs, associations, civil initiatives, and local community representatives, who criticise its speculative nature and lack of public participation. Furthermore, they argue that it is being used to justify port expansions in other parts of the city and render them more acceptable to the public.

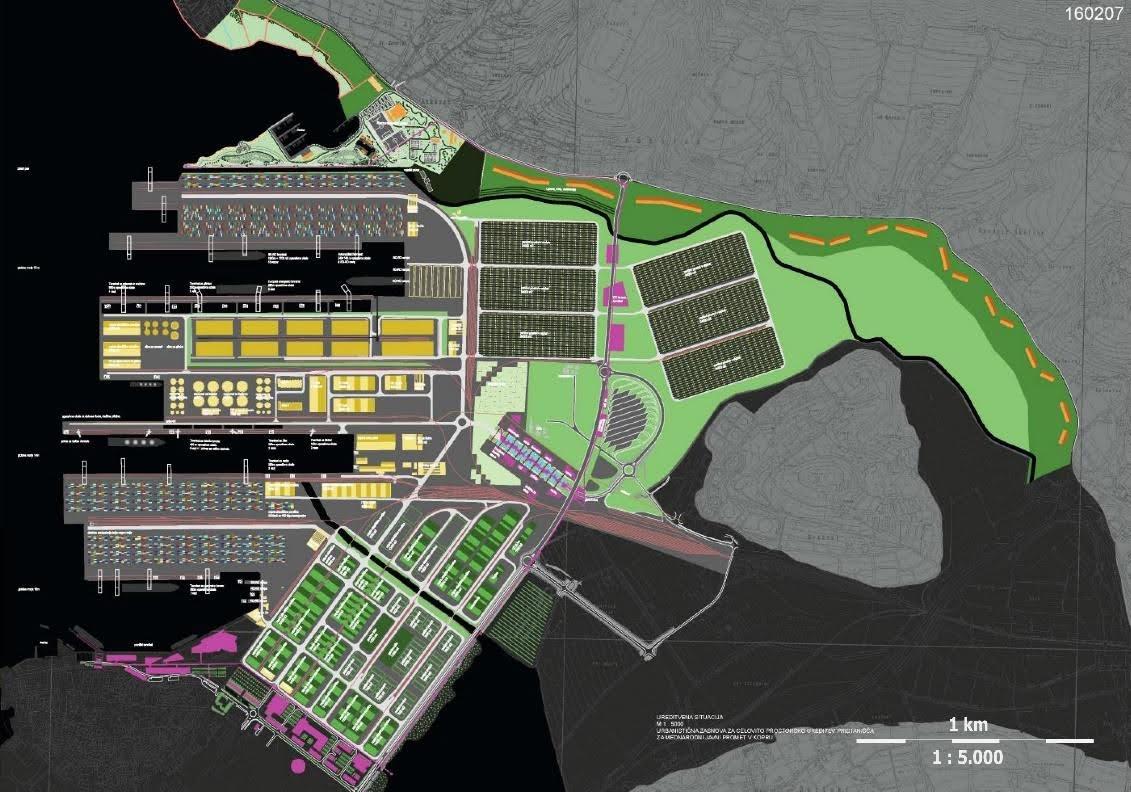

In Koper, the winning proposal for the integrated spatial development of the international port introduced the concept of a “green port”, proposing a climate-responsive port system that outlines planning solutions for transport, urban water management issues, sustainable energy, and permeability between the port and the city. Although the proposal was generally well-received, the formulation and implementation of the National Spatial Plan (NSP) for the Port of Koper (2011) that was based on this proposal, revealed specific power dynamics and triggered important changes in local governance. Concerns about the centralisation of power in the Municipality of Koper and environmental impacts related to the planned construction of the third pier even led to the split of the new municipality—Municipality of Ankaran—which now acts as an equal stakeholder in the port expansion procedures.

While cross-border collaboration between local civil groups and other newly emerged actors is still nascent, the general sentiment is clear: since the negative impacts of these two ports extend beyond national borders, there is a need to address shared challenges and opportunities together. The exchange of knowledge, experiences, and strategies to foster more collaboration and develop new place-based solutions could act as a catalyst for redirecting future port planning efforts toward a more integrated and inclusive direction that would benefit the entire region.

Note: This blog post is a partial summary of an article “Planning Ports in Proximity: Koper and Trieste since 1945” published in Planning Perspectives (Volume 39) in 2024:

https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2023.2301411.

Acknowledgement

Martin Valinger Sluga is a researcher and doctoral candidate, and Lucija Ažman-Momirski is an associate professor of urban design, both at the University of Ljubljana. This blog post has been written in the context of discussions in the LDE PortCityFutures research community. It reflects the evolving thoughts of the authors and expresses the discussions between researchers on the socio-economic, spatial and cultural questions surrounding port city relationships. This blog was edited by the PortCityFutures editorial team: Eliane Schmid.

References

European Commission. (1999). European Spatial Development Perspective: Towards Balanced and Sustainable Development of the Territory of the European Union. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Griesser-Pečar, T. (2007). Razdvojeni narod: Slovenija 1941–1945: okupacija,: kolaboracija, državljanska vojna, revolucija. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga.

Klabjan, B. (2019). Habsburg Fantasies: Sites of Memory in Trieste/Trst/Triest from the Fin de Siècle to the Present. In B. Klabjan (Ed.), Borderlands of Memory: Adriatic and Central European Perspectives, 59–88. Oxford: Peter Lang Ltd.

Mellinato, G. (2022). Complex Gateways: The North Adriatic Port System in Historical Perspective. In G. Mellinato, & A. Panjek (Eds.), Complex Gateways. Labour and Urban History of Maritime Port Cities: The Northern Adriatic in a Comparative Perspective, 9–31. Koper: Založba Univerze na Primorskem.

Panjek, A. (2007). “Dezintegracija med Trstom in Koprom: o razdruževanju gospodarskega prostora v Svobodnem tržaškem ozemlju = La disintegrazione fra Trieste e Capodistria.” In T. Catalan, G. Mellinato, P. Nodari, R. Pupo, and M. Verginella (Eds.), Dopoguerra di confine: progetto Interreg IIIA/Phare CBC Italia - Slovenia = Povojni čas ob meji, 443–465. Trieste: Istituto regionale per la storia del movimento di liberazione nel Friuli-Venezia Giulia.

Repe, B. (1998). Slovenska zahodna meja in ekonomsko vprašanje. Acta Histriae VI 6: 261–270.

Trupac, I. (2003). Lease of Pier VII as a Rudiment of the Single Port System. Promet - Traffic - Traffico 15(6): 361–369.