To understand the impact of grand challenges on port-city territories, PortCityFutures has established five thematic research groups, each led by core team members with support from PCF contributors. These themes—Coastal Cities, Small Ports Big Challenges, Everyday Infrastructures, Human-Centered Port City Transitions, and Mixed Methods and Design Strategies—connect theoretical, methodological, and case-study approaches. If you're interested in participating or collaborating, please explore the themes below and reach out to the respective thematic leads.

Thematic Research Groups

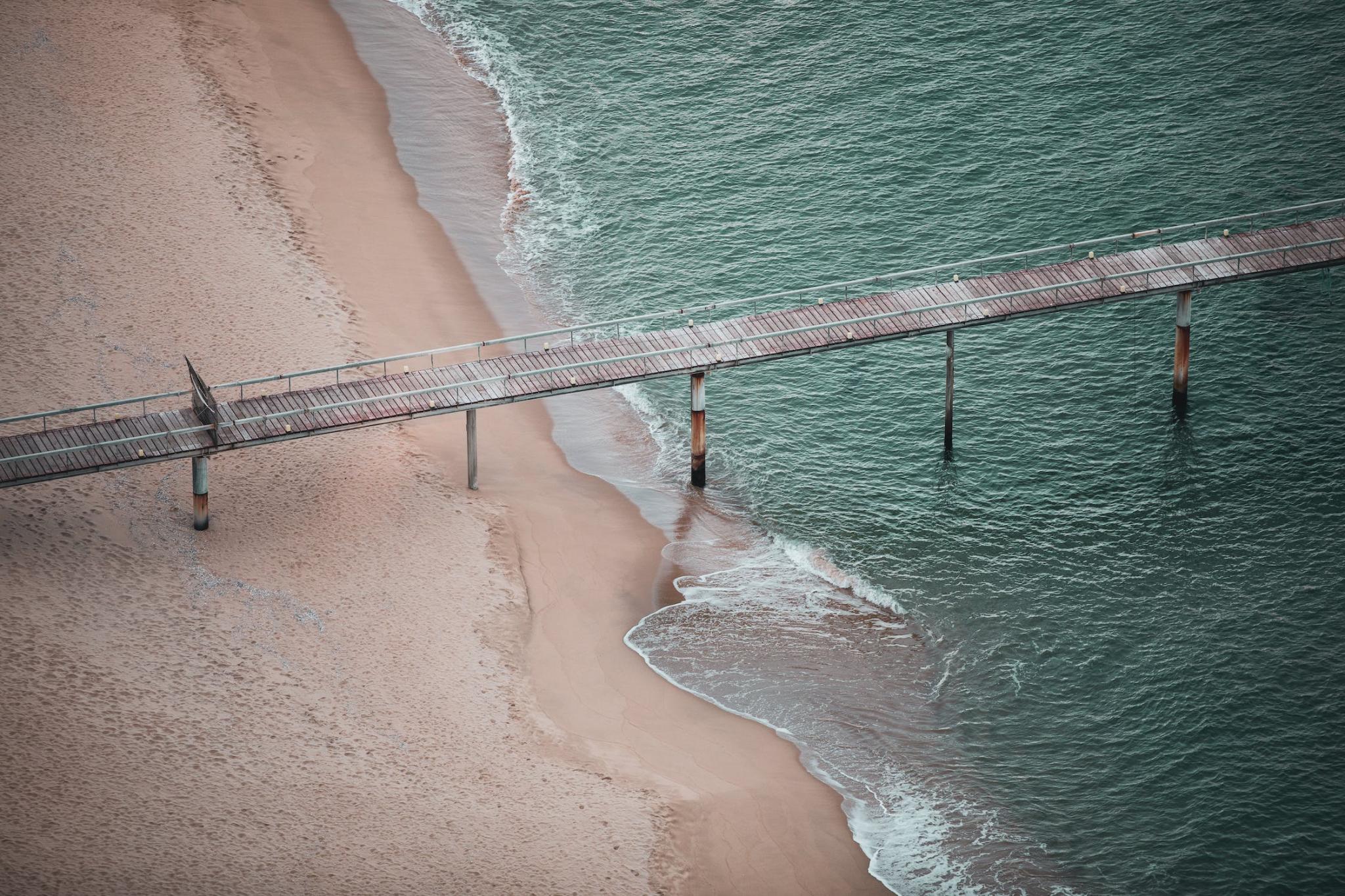

Coastal Cities

In this theme a dedicated research effort on the determinants of coastal port cities persistence in the history of taming the delta is proposed, with the potential to significantly advance the scientific understanding of economic sustainability of coastal port cities today.

The research will focus on the longue durée of the two-axis deltaic system and transport. Developing the repertoire in the spatial, morphological reciprocity between the two axes in order to – with research by design – project economical sustainable futures. The research thus couples the other themes in the PCF research in this specific approach.

Small Ports Big Challenges

Despite their modest size, small port cities play an important role in regional economies and societies. They have multiple functions within their ecosystems and often cooperate with larger ports in the region. The focus on large, often coastal, port cities has overlooked small ports. Small port cities face many complex challenges, including infrastructure limitations, financial constraints and intense competition. They need comprehensive planning and policy support to address issues such as energy transition, sustainability and regulatory compliance. Research on these port cities should be transdisciplinary and focus on their long-term development and interaction with regional contexts and networks, with the aim of identifying opportunities for cooperation and upscaling, and addressing their specific challenges.

Everyday Infrastructures

Ports are infrastructural hubs connecting sea and hinterlands. These material structures are shapers of economic flows of goods, people and knowledge and they are embedded in geopolitical dynamics. But what goes into the making of these infrastructures? How are they embedded in everyday practices of state authorities, corporate designers and constructors? How do they affect the lives of citizens living in their vicinity and the users of transport corridors? For studying how global port developments are grounded in human experiences and daily practices – both at land and at sea – we need to approach infrastructures not as objects, but as relational networks which are constructed, maintained, used as well as contested.

Human-Centered Port City Transitions

Cities and port cities have the unique ability to create the conditions for society to prosper. Port cities play a vital role in fostering societal prosperity. However, the growth of port cities poses challenges to the ecosystem and requires a strategic balance of resources. The symbiotic relationship can play out positively but also negatively depending on how the port city goes about with the carrying capacity of the ecosystem to support human activities in a densely populated and highly industrialized port city space. The fragmentation of governance and the interlinkages between adjacent functions on the interface can turn into conflict if not managed well. A reconceptualization is needed to reconnect the relationships between ports, cities, and people.

Mixed Methods and Design Strategies

PortCityFutures has over the past couple of years started to develop new shared methodologies to connect space, society and culture. Building on this trajectory, the PCF research theme on Methods takes the lead in further developing forms of analysis that are fundamentally spatial, and take social, affective, mnemonic and heritage values (to name a few) explicitly into account. We are focussing on multiple forms of mapping (GIS, mental, stakeholder, etc.), as well as sensorial and design research; and we are revealing the subjectivity of stakeholders’ perspectives by other means, allowing inequality and conflicts of interest to be foregrounded in building theory, and creating the means by which societal actors may be able to identify, address and ideally resolve spatially grounded conflicts of interest.