Carola Hein, Maurice Harteveld, John Hanna, Paolo De Martino, Muamer Tabaković, Carlien Donkor, and Libera Amenta

This field trip was a collaboration between the Netherlands Institute Morocco (NIMAR), the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment of Delft University of Technology (TU Delft), PortCityFutures, and the Ecole Nationale d’Architecture de Rabat (ENA Rabat).

This year’s Urban Archipelago graduate design course focuses on water and public space in Moroccan cities. We are building on and advancing the methods that we developed during last year’s exploration of the Italian city of Trieste on the Adriatic coast, including, among others, biographies of place, micro-narratives, and guided imagery of water within urban landscapes. Once again we challenge students to rethink the spatial, societal, and cultural practices of today by learning from the past and envisioning sustainable futures by design. The effects of urbanization and climate change are also increasing in Morocco; however, here in particular, the lack of water will have a long-term effect on public areas and urban life. After visiting Trieste, we concluded that personal experience is key to understanding the role that water plays in our lives. This insight remains valid. It promised to be an immersive exploration into the multifaceted dimensions of water in the Moroccan cities of Rabat, Salé, Fes, and Tetouan.

The program kicked off in Rabat amid appreciably higher temperatures, no rainfall, and relatively moderate humidity of 68%. The participating students from Delft University of Technology (TU Delft) arrived full of fascination and tentative viewpoints shaped by their pre-travel desktop research. They presented their concept ideas and received feedback from their hosts at the Netherlands Institute Morocco (NIMAR). The presentations sparked insightful discussions, enriched by the local perspectives of the Rabat students and the critical reviews from the international group of academic supervisors.

Léon Buskens, chair of Law and Culture in Muslim Societies at Leiden University and director of the NIMAR, followed with a lecture on the cultural—both historical and contemporary—aspects of water management and control in Moroccan cities, highlighting its powerful system for shaping and sustaining urban life. Ouafa Messous, professor of Urban Design and Architecture at Ecole Nationale d’Architecture de Rabat (ENA Rabat) and Deputy Director in the Department of Social Housing and Land Affairs, then delved into the socio-cultural significance of water, emphasizing its role in daily rituals, religious practices, and communal life. She highlighted how these practices are spatialized in urban and architectural design and how they manifest in public spaces. A resounding statement from her lecture, reflecting on the drought conditions in Morocco, was that many Moroccans believe that “the water will come back again.”

The group then boarded a bus to Azafran, an oasis on the banks of the Bouregreg River, where we were served lunch at the Med-O-Med Gardening School restaurant, near the city of Salé on the opposite bank facing Rabat. The group was introduced to the green premises, spanning over 8 hectares, dedicated to creating green public micro-climates and promoting propagating planting and irrigation techniques. The school provides opportunities for community development as well as education and training for young people at risk of social exclusion. The visit was followed by an afternoon dedicated to following the Bouregreg River upstream, studying the contextual materiality of the urban water systems and practices. We explored agricultural activities in the hinterland and infrastructural projects such as dams, reservoirs, sewage treatment plants, and waste management, along with traditional inland fishing activities, all of which shape the region’s hydro-social conditions. These explorations highlighted the tensions between natural and modern systems, as well as between lavish and modest lifestyles.

In the evening, Jeroen Roodenburg, the Ambassador of the Kingdom of the Netherlands to the Kingdom of Morocco, hosted the delegation for a reception at his residence for an evening of socializing and cultural exchange. His compound, in keeping with tradition, featured a lush garden with small water fountains and features, which raised questions and awareness about water inequality and scarcity within the city and beyond.

On the second day, we embarked on a journey to Fes, where the view from the Tombeaux Mérinides on the hills offered a perspective of the ancient city nestled in the valley. The sprawling urban tapestry is woven with the threads of its society and culture. The Oued Fes, or Fes river, naturally runs through the lowest part of the urbanized landscape. At some distance, southwest of the city, we saw Ras al-Ma, or “head of the water”, where the river springs. This fresh natural water runs first through the historical Royal Palace, with its main branch continuing through Fes el-Jdid before approaching Fes el-Bali. From this vantage point, the sharp separation between the new housing development and the medina was particularly remarkable.

Guided by Mounir Akesbi, the inspector of Historical Monuments and Archaeological Sites of Fes, and Abdelbasset El Fallous, the City Architect, the group was introduced to the particularities of water management, control, and distribution within the labyrinthine public space network inside the medina's walls. They also explained a systemic approach to the urban and architectural manifestation of water in daily life. Water, they demonstrated, was not just a resource but a productive force of Fes’s urban fabric, physical reality, and social practices. Among other sites within the city, we visited the tanneries as a witness of this integration, as well as the Bou Inania school, one of many Islamic institutions that contribute to the Fes’s reputation as a city of scholarship and innovation. Nearby, the Dar al-Magana (Water Clock) was historically used to sound prayer times. In the afternoon, the students were encouraged to explore the city on their own to gain a full experience of Fes.

The third day began with a trip to Tétouan, known for its unique Skundo water system. The group traveled by Al Boraq (Morocco’s high-speed rail) from Rabat to Tangier, and then by bus to Tétouan. Nadia Erzini, an Urban Design and Architectural Heritage expert for this city, introduced the intricate Skundo system that has sustained Tétouan for centuries. She gave a lecture on the historical mansions in the medina, including a visit to her own family home, which featured an enclosed courtyard and water fountains. The Skundo system draws its supply from a belt of springs in the surrounding mountains, like Jbel Moussa and Jbel Dersa, and services public fountains, wells in public spaces as well as public buildings like mosques and hammams. It also provides water to riads or courtyard houses. In general, Moroccan houses often feature inward-facing designs with few windows, concealing spaces like courtyards and gardens from the public eye.

This sense of social secrecy and privacy reflects the cultural emphasis on family life and personal space. Both Delft and Rabat students noted how this intimate spatial arrangement allowed for quiet, contemplative environments in the middle of the bustling city, producing different sensorial experiences. After lunch at Riad El Reducto, the fieldwork continued under the guidance of Khalid Rami, an expert in Cultural and Natural Heritage Planning of Tétouan, and M’hammed Benabboud, a local expert in Political and Social History. They brought rich insights into the traditional ways of managing water distribution in semi-arid regions, showcasing an ingenious example of sustainable water infrastructure cleverly integrated into the urban fabric. The system maintains a delicate balance between public utility and private sanctuaries—another historic trace of urban elements and architectures designed for both beauty and secrecy. It was refreshing to see a local resident fetching water in his bucket from one of the many Skundo cisterns scattered around the city, which are still providing free, accessible potable water in the medina.

Reflecting on these experiences, the dual nature of Moroccan urban design became clear: a blend of openness and sharing in public spaces contrasted with guarded secrecy in what might be considered private places. This trip deepened our understanding of how water systems and urban and architectural designs are interwoven with cultural values and societal norms, creating a harmonious living environment. Such observations contrast with the unsustainable practices of bottled water, hidden water distribution in Modernistic bathrooms and kitchens, and some incredibly filled swimming pools in times of local water shortage.

On the fourth day, a student design workshop, led by academic staff from both Delft and Rabat universities, took place at ENA, Rabat. This workshop aimed to foster a rich cultural exchange among students, analyzing the intricate relationships between land, sea, and river, as well as between water and culture. It focused on the diverse hydrological impacts on contemporary societies and territories, among others. Ouafa Messous emphasized the critical role of water in our world, particularly as climate change and urbanization dramatically reshape landscapes. As the local academic expert, she highlighted the importance of understanding the spatial and cultural dimensions of water, setting the stage for a deep dive into the complexities of water management and urban design.

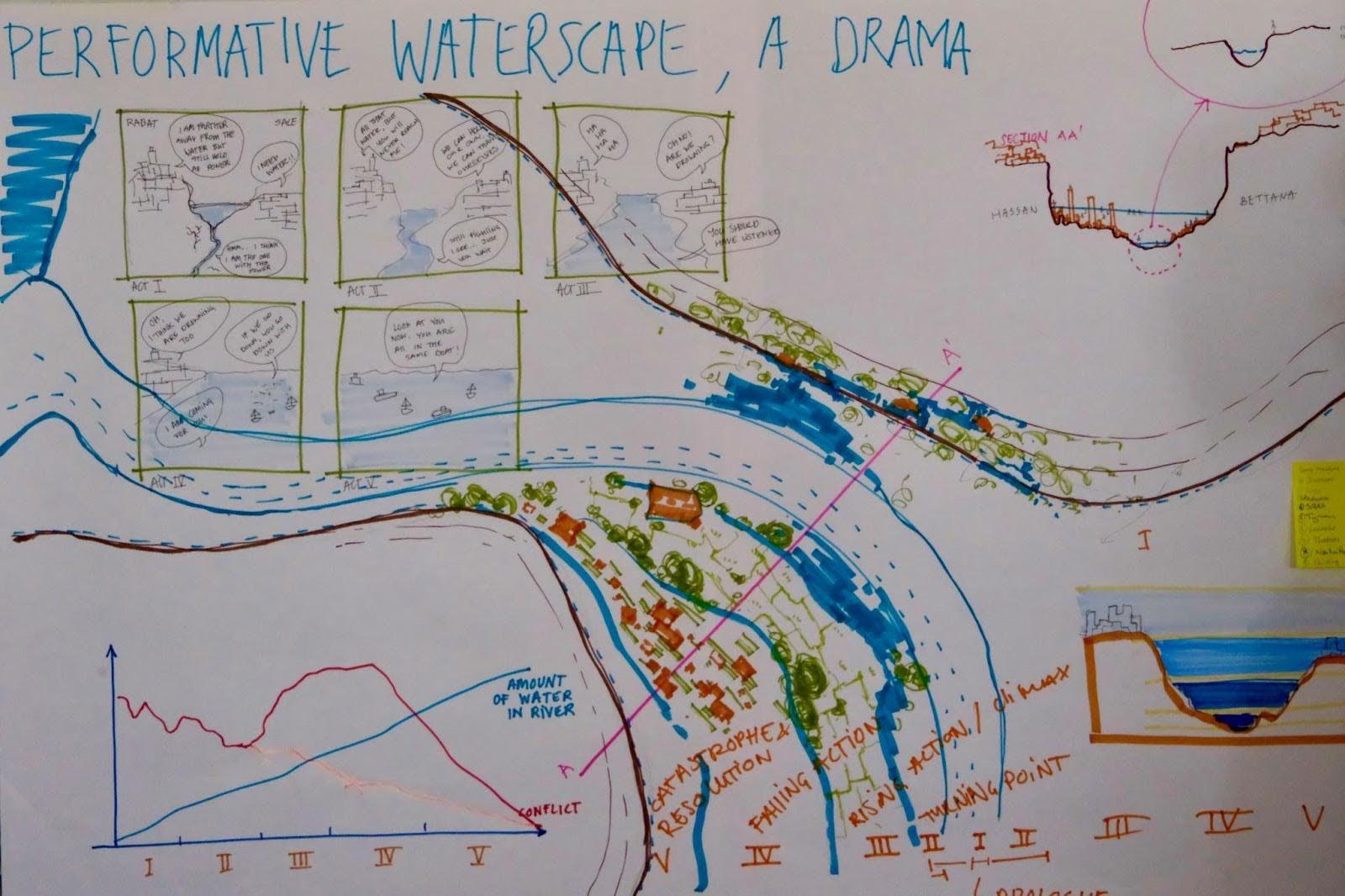

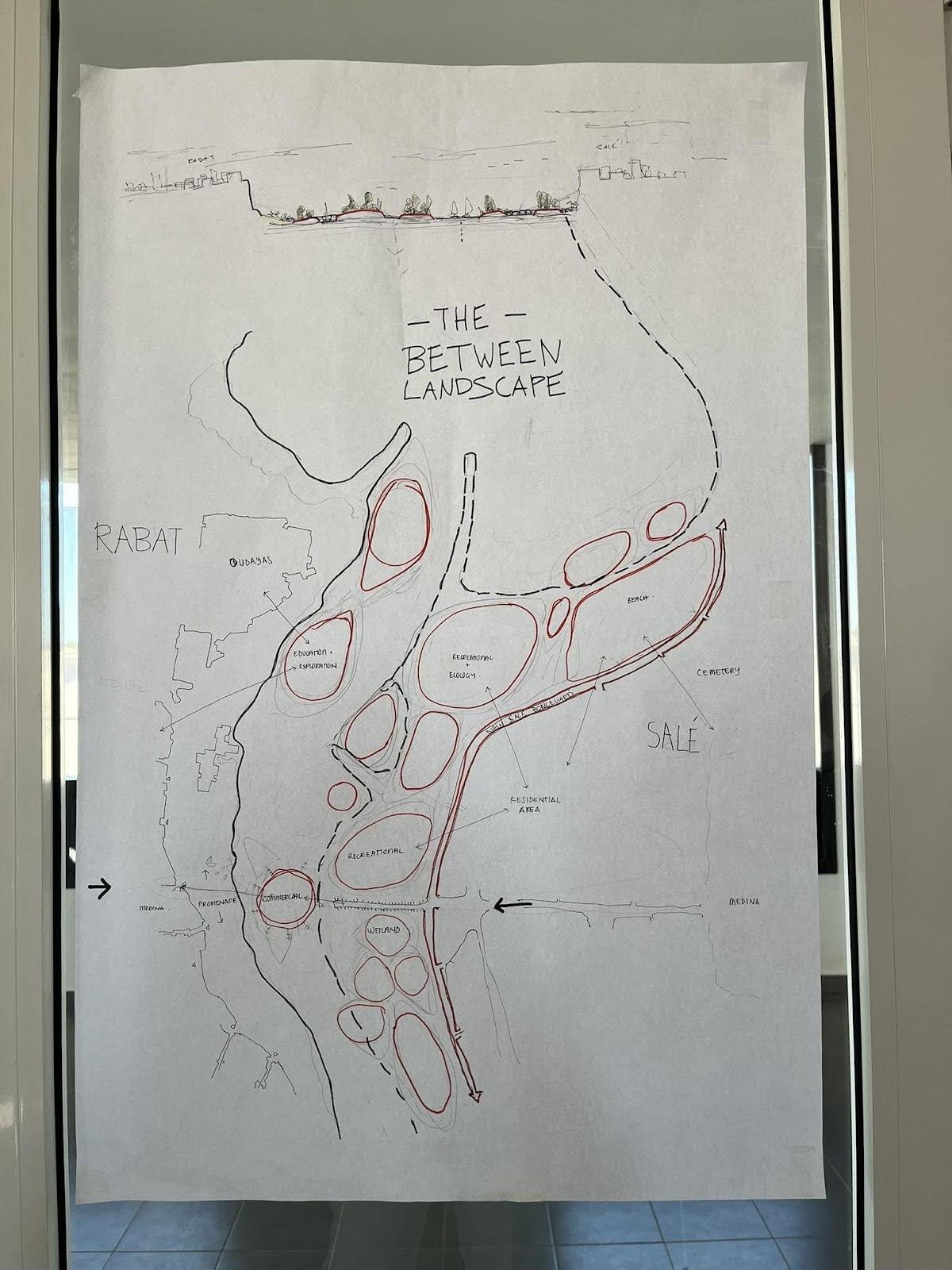

Mixed student teams explored various aspects of water heritage in the public space in experimental future scenarios for how the cities of Rabat and Salé could coexist with water and with each other again. The workshop focused on the multiplicity of water spaces. Students delved into the cultural understanding of how water could reshape the physical, social, and ecological landscapes of both cities. They identified critical elements like edges where land and water meet, spatial patterns created by water flow, and abandoned spaces related to water that could be reused differently.

These explorations were not just academic exercises; they were opportunities to envision new, adaptive scenarios for urban environments facing or likely to experience changing water conditions. Discussions were vibrant and synergetic. Students from different cultural backgrounds shared their experiences and perspectives, enriching the collective understanding of the role of water in designing for tomorrow. They sketched ideas and debated the best approaches toward resilient, water-conscious urban environments, with an emphasis on what can be achieved in public space and blending traditional knowledge with contemporary design principles.

The results of the workshop were nothing short of provocative. The students pushed the boundaries of traditional design, presenting extreme narratives on how to live with water. Some envisioned floating medinas, entire neighborhoods rising and falling with the tides, seamlessly integrated into the water landscape. Others crafted dramatic stories of urban resilience, where cities adapted to frequent flooding through innovative infrastructure and community practices.

Some students proposed practical spatial solutions for sustainable water management, control, and distribution, highlighting the importance of preserving cultural practices while adapting to new societal challenges. Others presented provocative narratives aimed at deconstructing existing dominant Modernistic beliefs and constructs. In the end, each team showcased their vision of a future where cities are harmoniously integrated with their water systems.

The students not only gained technical knowledge but also developed a profound appreciation for the cultural and social dimensions of water, especially within the local context of Rabat and Salé. Departed with their newfound insights, they were ready to apply what they had learned and continue their journey of designing with water, carrying forward the lessons and connections made.

The last day was spent in Salé, where Mohammed Krombi, the local City Architect, welcomed the group at Bab le-Mrisa, the water gate. He recounted the historical presence and significant absence of water and gardens in this medina. Despite its proximity to the sea and river and the presence of river harbors behind its main gate, clean water historically came and is still coming from long distances via aqueducts. Water scarcity led to a limited number of water distribution fountains at key community locations.

Ultimately, the research visit concluded at the historic Kasbah of Rabat, where the delegation said their goodbyes over mint tea and Moroccan pastries. The setting was picturesque: overlooking the estuary with its blend of natural and man-made features and activities; water was at the heart of conversations throughout the trip. As they enjoyed the serene view over the Bouregreg one last time, they saw the luxury real estate across the estuary juxtaposed with traditional fishing activities and reflected on yet another day's experience about the critical roles of water in shaping Moroccan cities and life. The mint tea, a staple of Moroccan hospitality, added a touch of warmth and tradition to the moment.

The afternoon was left free for personal exploration of Rabat. Some wandered through bustling souqs, picking up souvenirs such as miniature water fountains, while others immersed themselves in Moroccan culture. A few adventurous students visited a traditional hammam, experiencing first-hand another space of water-related rituals in Moroccan culture. The hammam, with its intricate bathing practices and emphasis on purification, provided a profound and intimate connection to the theme of water, highlighting its significance beyond mere utility.

As the day drew to a close, our journey, which had woven together education, research, and the timeless presence of water in the Moroccan cities—both visible in public spaces and hidden elsewhere—came to a temporal end. Back home, we continued to work on these cases, which were presented in the final students' projects for the course Urban Archipelago. Designing for Maritime Mindsets. To be continued.

Acknowledgments

This blog post has been written in the context of discussions in the LDE PortCityFutures research community. It reflects the evolving thoughts of the authors and expresses the discussions between researchers on the socio-economic, spatial and cultural questions surrounding port city relationships. This blog was edited by the PortCityFutures editorial team: Yi Kwan Chan.