Artemis Rovoli

Department of Architecture, Delft University of Technology

As a born and raised Athenian, I strive to find the best swimming spots in the city every summer, especially with the ever-rising temperatures each year. However, these spots seem to become harder to find, with many beaches being privatized or only open to exclusive members. As a result, even though I live in a city surrounded by water, I rarely find myself spending time by the water at all. The Athenian Riviera stands as a testament to the relation between urban development and leisure culture, showcasing the architectural evolution spanning over a century. Within this dynamic cityscape lies a narrative of shifting socio-economic norms, where the development of the waterfront has affected the swimming habits of Athenians. This blog post offers an insight into the birth of swimming culture in Greece in the middle of the 1800s and showcases how the port of Piraeus and its surroundings became the starting point of a long and complicated expansion on the coast.

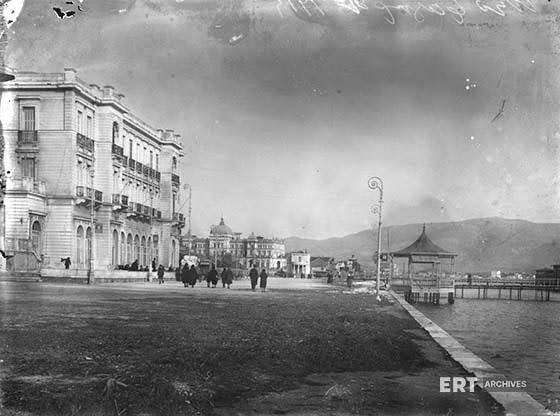

It is hard to imagine now, but before the 1800s the Greeks did not swim in the country’s crystal-clear blue waters. Swimming in the sea coincides with the birth of The Hellenic Republic in 1830 (Gulnara Sadraddinova, 2020), when a few years later Queen Amalia attempted her first dive into the sea in Tzitzifies in 1834 (Cholevas, 2014). In 1834-1835, Piraeus was chosen as the leading port of the capital, and a few years later, mayor Kyriakos Sefiotis opened the first organized beach (Cholevas, 2014). However, the term “beach” refers more to public baths, i.e., it is described as wooden platforms projected into the water, from which people dive. Because of the growing influx of visitors in Piraeus, the newly formed Greek government appointed British engineer Edward Pickering to build the first railway line in Greece, connecting the center of Athens to the Port City of Piraeus in 1869. The existing industry benefited from the creation of the train line because of the accessibility of the workforce (Belavilas, 2002), which divided the port’s urban plan into two parts: the industrial on the west and the urban on the east.

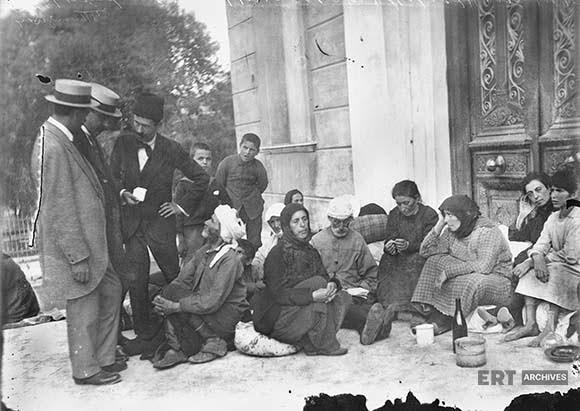

Slowly but steadily, working-class housing created a stylistic and simultaneously practical division of the port, which initiated the expansion towards the south-east in Neo Faliro. The construction of neoclassical public buildings, including megarons, a food market, and the stock exchange (Belavilas, 2002), led to the rise of culture-centered areas and the construction of major architectural works like the "Aktaion," "Grand Hotel de Phalère," and "Tarantella," which attracted Athens' bourgeoisie to build summer houses nearby. There, different social classes would meet at the promenade, and the culture of walking along the water for socializing and leisure was born by people enjoying the restaurants and architectural attractions of the area. However, the influx of refugees to Greece’s main port during the Greek-Turkish war in 1922 (Belavilas, 2002) changed the character of Piraeus because of the lack of adequate infrastructure to accommodate the growing population. In addition, the industrial activities led to heavy pollution in the area and drove the upper class to move further into the south (Belavilas, 2002).

The 1950s was the decade when mass tourism was established in Europe, something that influenced the Greek government to expand and develop the infrastructure to accommodate incoming tourists (Cholevas, 2014). Private establishments, alongside public works, significantly influenced the coastline and people's attitudes toward swimming. Astir Beach in Vouliagmeni exemplifies the transformation of a public beach into a luxury resort, reshaping the area’s character and surroundings. Situated in one of Attica’s most beautiful natural landscapes, with calm waters and pine forests, Astir Beach naturally attracted high-end investors. It became home to the Riviera’s most prestigious beach facilities, further elevated by the innovative architecture of Pericles Sakellarios, A. Georgiadis, and C. Decavallas between 1959‐1961 (Fessas-Emmanouil & Sakellariou-Herzog, 2006). Over time, private bungalows, hotels, and restaurants were added, cementing the peninsula’s status as a high-end destination catering to foreign tastes (Nennes, 2021). This development underscores the growing influence of financial incentives on the waterfront's image, with swimming emerging as a symbol of luxury, relaxation, and vitality. As a result, going to the beach became more than a pastime; it evolved into a social attribute, reflecting deeper cultural values.

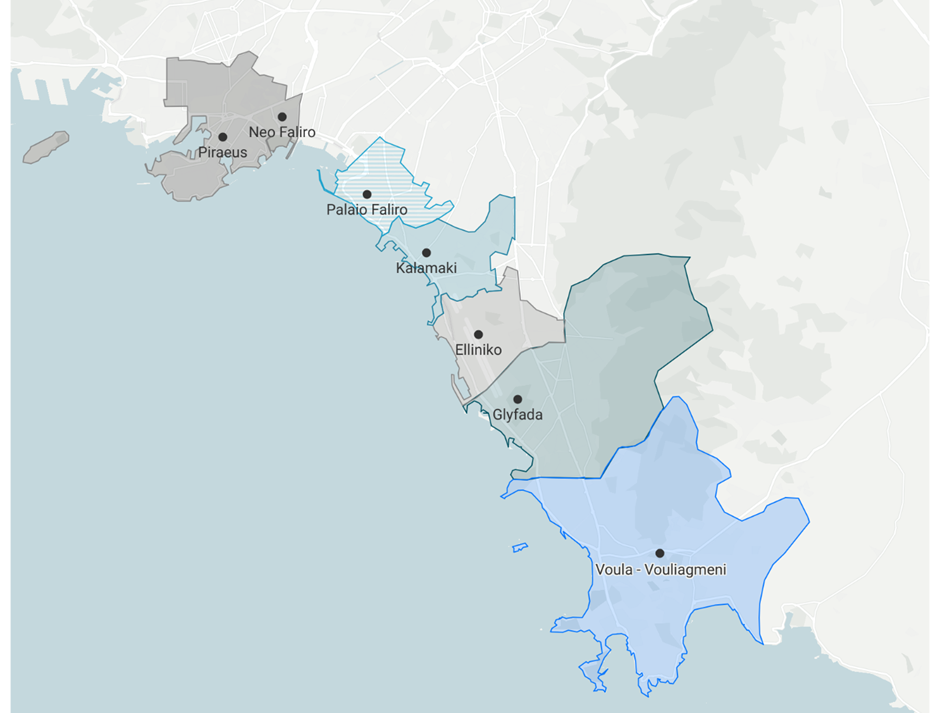

Nowadays, as we travel along the Athenian coast from the bustling port area towards the serene shores of Astir Beach, a notable shift in waterfront dynamics becomes evident. Closer to the port, access to the water is relatively easier, facilitated by lower fees to the beach and robust public transport connectivity to the city center. According to interviews with locals, this area is popular for swimming; however, concerns are raised about the water quality. Moving southward, the architectural density gradually diminishes, giving way to a more tranquil environment characterized by nature buffers between the road and the sea. Here, beach access tends to be more privatized, with free beaches discreetly tucked away and known only to a select few. Finally, at the beaches of Vouliagmeni and Astir, the natural landscape is more prominent. However, exclusivity rises significantly, with establishments charging high entry fees or allowing access solely to members. Thus, while the southern coastline offers a pristine natural environment, the privatization and exclusivity levels pose challenges to inclusive access for all beachgoers.

The evolution of swimming culture in Athens reflects a broader narrative of urban coastal development and societal changes. Swimming does not seem to be the driving force for the development of the coast, but rather water-related activities and consumerism. This assumption is supported by the plans for the redevelopment of the former Ellinikon airport. These grounds were once the driving force for the creation of Posidonos Avenue in the 1950s (Cholevas, 2014), and today they are the ground for the development of Europe’s largest coastal park project (Florian, 2023). Ellinikon’s focus on exclusivity and commercialization creates worries about its impact on societal inclusivity and the waterfront's core value. The debate highlights the complex interplay between economic development, urban planning, and social equity in shaping the future of coastal landscapes.

Overall, the urban waterfront development of Athens is a complex subject since its influence touches various fabrics of society. The importance of its utilization has historically been evident for interdependent reasons of profitability, recreation, and image promotion to the rest of the world. Small, local qualities and principles, such as swimming, evolved along with the waterfront’s transformation and have been embedded into the city’s culture. The fragile act of balance between locality and financial gains affected the accessibility to the shore for the Athenians. Furthermore, the role of swimming is fading away from the urban planning of the Athenian Riviera since its transformation is driven by commercial international trends, making it harder for Athenians to find a spot where they can peacefully swim.

Acknowledgments

This blog post has been written in the context of discussions in the LDE PortCityFutures research community. It reflects the evolving thoughts of the authors and expresses the discussions between researchers on the socio-economic, spatial and cultural questions surrounding port city relationships. This blog was edited by the PortCityFutures editorial team: Wenjun Feng.

References

Belavilas, D. N. (2002). THE PORT OF PIRAEUS FROM 1835 TO 2004. Patrimoine de l’ Industrie/ Industrial Patrimony TICCIH-ICOMOS-Ecomusee de La Communaute Urban Le Creusot Montceau Les Mines, no7/2002, 75–82.

Cheirchanteri, G. (2019). Transformation in the Wider Industrial Coastal Region of Saint George, Western of Piraeus Port in Athens. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 471, 102060. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/471/10/102060

Cholevas, M. (Director). (2014). “August at the beaches of Athens” [Series ]. Hellenic Broadcasting Corporation (ΕΡΤ).

Fessas-Emmanouil, H., & Sakellariou-Herzog, E. (2006). An architect’s vision, P. A. Sakellarios (1st ed.). Potamos Publishers.

Florian, M.-C. (2023, October 20). BIG Unveils Design for New Residential Development in Ellinikon, Europe’s Largest Urban Regeneration Project. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/1008612/big-unveils-design-for-new-residential-development-in-ellinikon-europes-largest-urban-regeneration-project

Georgouli , St. (2019). Investigation of the impact of tourism on the social and cultural environment of the host sites. The case of Greece [MSc Thesis]. https://hellanicus.lib.aegean.gr/handle/11610/19853?show=full

Gulnara Sadraddinova. (2020). Establishment of the Greek state (1830). Granì, 23(11), 91–96. https://doi.org/10.15421/1720105

Nennes, G. (2021, July 22). Αστέρας Βουλιαγμένης: Η ιστορία του θρυλικού συγκροτήματος. AthensVoice. https://www.athensvoice.gr/life/life-in-athens/722816/asteras-voyliagmenis-i-istoria-toy-thrylikoy-sygkrotimatos/

Vaggelas , G., & Pallis, T. (2023, May 17). Port Connectivity; Piraeus in the global sea transport network – PortEconomics. Port Economics. https://www.porteconomics.eu/the-piraeus-port-connectivity-in-the-global-sea-transport-network/