Bryan Castillo Dávila

In the free online course (Re)Imagining Port Cities: Understanding Space, Society and Culture, learners make a portfolio addressing the spaces, transitions, challenges, stakeholders and values of a port city territory of their choosing. We motivate the learners to reflect on their learning and invite them to present their findings in a blog. In this blog, learner Bryan Castillo Dávila writes about Peru’s Callao, a port city with enormous potential for urban development, but nevertheless also still facing challenges that show the need to have more diverse actors and visions coming together around the decision-making table.

The port city of Callao is both a city with a rich past and a huge potential for the future. Callao is located on the central coast of Peru and its coastline is over 40km in length, consisting of a series of islands with a vast natural marine ecosystem. The city’s coastline sits right next to the most important port and airport in the country. As evidenced by the Ministry of Culture of Peru, Callao, like any port city, has a direct relationship with the sea through the thousands of years of human presence on its territory (Ministry of Culture of Peru, 2016). This past has left Callao with pre-Hispanic architecture that includes the Oquendo Inca palace, the Oquendo Inca trail and a walled city located right underneath the contemporary city layer.

Callao is one of the 25 regions of Peru, which provides the city with a series of legal and administrative benefits for its potential growth as a global city. Recently, this potential has been further recognized by local and national governments, and is being acted upon by improving the port region but not necessarily the cityscape. The city is immersed in a narrative subordinated to the discourse of the country’s capital city, Lima. In other words, from Lima, Callao has been granted the ‘unique role’ of a logistics pole serving the capital city, as confirmed in the Metropolitan Development Plan of Callao 2040 (PDM Callao 2040, 2021), a context that seemingly has stopped any attempt to improve the city itself since the end of the 20th century.

Callao has a long history of urban growth and development. Although the current city is the product of the overlapping of different urban layers, including pre-Hispanic settlements, the historic center of the city has a relatively recent urban fabric, due to the city being rebuilt after a 1746 tsunami. A territorial timeline of Callao (see Figure 2) was made using historical information and maps, which demonstrate that from the beginning of Callao’s history, the city hosted diverse and close relationships between its urban and port activities (Quiroz Chueca, 2007).

After 1746, the history of the city took a new turn. Urban growth coincided with port growth. Urban development became harmoniously articulated with political, social and cultural constructions in Callao. Callao became an autonomous city in 1836 and in 1857 obtained the category of Constitutional Province. During the 20th century, Callao consolidated itself as a truly developed city. Towards the late 1970s and early 1980s, however, Callao was affected by a series of difficult situations that the country was going through: among others, an economic crisis and period of internal conflicts that included terrorism and the rise of drug trafficking. By the time the port of Callao was privatized, these occurrences managed to dismantle the urban dynamics that had developed until then (Paz de la Vega, 2017).

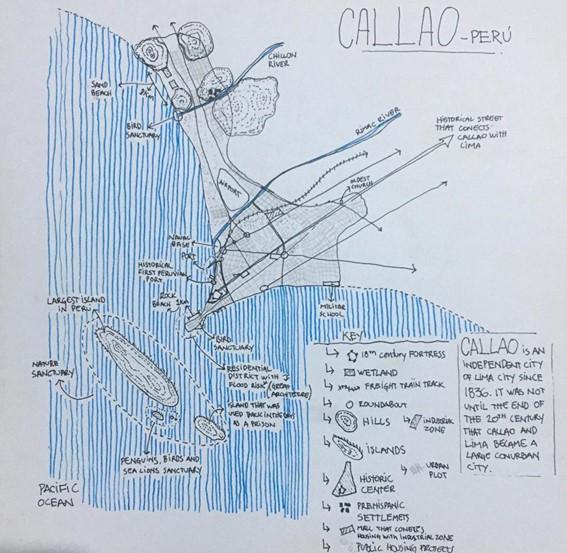

Now, the city of Callao has grown to nearly 150 km2 and more than 1 million inhabitants, thereby becoming the third largest city in Peru. Although it is strongly linked to the sea and has natural ecosystems such as hills, wetlands, rivers and islands (see Figure 3), the city has not yet achieved a sustainable development that fully understands and includes these ecosystem spaces as part of its urban development. This is largely due to the aforementioned role of logistics yard that the capital city has imposed on the port city, as architect Ortiz de Zevallos also mentions (PDM Callao 2040, 2021, p.8-9).

In the planning instruments of Lima, such as the Metropolitan Development Plan of Lima 2040 (PLANMET 2040, 2022), it is possible to see how the urban development model of Lima has as its main guideline the articulation with the city of Callao for logistical purposes, even when this means imposing itself on or across territorial, urban, administrative and political boundaries (PLANMET 2040, 2022, p.118). Callao and Lima are two big cities that have formed an urban conurbation. Geddes (1915) famously refers to this as an urban development area where a series of different cities grow up to meet each other. Although this concept refers to a relationship of common interests, the relationship between both Peruvian cities has in reality meant a subordination of one over the other. This also directly links to consequences of thinking of a port city exclusively based on its logistical role. The last case of an oil spill in the Callao sea (see Figure 4), for instance, was a scandal, but it nevertheless was not enough to encourage the government to further talk about the ecosystem and urban needs of this city in relation to logistics.

Industrial and logistical roles keep having a great impact on Callao. The dumping of tons of oil on the coast of Callao due to mismanagement by the Repsol Company, whose factories are located next to fragile nature spaces, is another example of this. This disaster has been destroying a large part of the natural ecosystem of the city, even putting people who live nearby at risk of pollution.

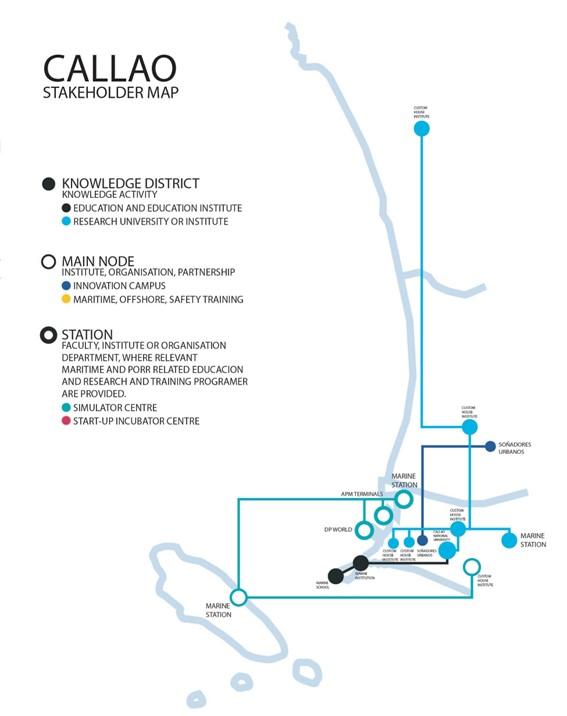

This leads to an important reflection: what is more important, the people and natural ecosystems, or the economy of logistics of the city? In Callao’s city-port relation, there is a predominance of stakeholders related to the port and logistics, while only a small number of organized citizen actors attend to the urban and citizen's needs today. Understanding that citizen groups often also lack the level of impact, scope and/or power compared to industrial actors such as DP World or APM Terminals (see Figure 5), it is evident that current decisions in Callao on planning and improvements of the city-port relation fall mainly towards the port’s logistical needs. Reducing the city to simply ‘the port’ has become a powerful way of making the city invisible not only to the country or the world, but also to the citizens themselves.

In Callao, it is possible to see that reducing the city merely to the port does not even allow the city to capitalize on tourism through the Callao port or airport. In addition, it creates a perfect scenario for projects like the building of an elevated expressway that connects the Callao airport only to the city of Lima, thereby further harming Callao itself by roofing three of its districts and destroying an important avenue that has qualitative public spaces. There is also the South Pier of Callao port expansion project, which blocks the sea view from one the most important ceremonial plaza in Callao, or a private recreational marina project that consists of a series of yachts parked in front of natural wetlands and eliminating three public beaches.

The challenge for port cities therefore lies in being able to create and maintain citizen stakeholders that always look for equality in the development of the port city, in such ways that the urban, natural ecosystem and logistical dynamics remain in balance and keep the citizens’ needs on the agenda. After all, a city is made by the people, their traditions, history and memory, and the natural territorial aspects that shape these.

Finally, it is important to mention that under a certain urban vision, a city can accept or reject certain changes, projects, dynamics, etc. In the case of Callao, it remains possible to see an option for future improvement through the Metropolitan Development Plan of Callao 2040, a plan that for the first time may let the city cease to be seen as only a port and instead finally invites us to see Callao as a true metropolitan port city.

Acknowledgement

The free online course (Re)Imagining Port Cities: Understanding Space, Society and Culture runs on the edX platform. This blog has been written in the context of discussions in the LDE PortCityFutures research community. It reflects the evolving thoughts of the author and expresses the discussions between researchers on the socio-economic, spatial and cultural questions surrounding port city relationships. This blog was reviewed and edited by Foteini Tsigoni and Vincent Baptist.

References

Geddes, P. (1915). Cities in Evolution. Williams & Norgate.

Ministry of Culture of Peru (2016). “Sitio Arqueológico Chivateros camino a ser Patrimonio Cultural de la Nación.” https://www.gob.pe/institucion/cultura/noticias/48866-sitio-arqueologico-chivateros-camino-a-ser-patrimonio-cultural-de-la-nacion.

Paz de la Vega, A. (2017). “García, Kouri y Moreno son los responsables de la situación en el Callao” [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qwNMiaqhRvI.

PDM Callao 2040 (2021). Metropolitan Development Plan of Callao 2040. https://issuu.com/pdmcallao2040/docs/pdm_callao_2040_resumen_ejecutivo.

PLANMET 2040 (2022). Metropolitan Development Plan of Lima 2040. https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/3851856/Ord.%202499-2022%20%2B%20PLANMET%202040%20%281%29.pdf.pdf?v=1668791607.

Quiroz Chueca, F. (2007). Historia del Callao. Fondo editorial del pedagógico San Marcos.