Annisa Ariyanti

Department of Architecture, Muhammadiyah University of Surakarta, Surakarta, Indonesia

Annisa Ariyanti is a freelance architect currently based in Mimika Regency, Central Papua, Indonesia. She completed her architectural engineering degree at Muhammadiyah University of Surakarta in 2017. Annisa has witnessed the shifting economic and political landscape that continues to shape the environment and future generations. This article is not intended as a scientific report but rather as a reflection of her personal observations and understanding of the situation surrounding tailings in Mimika Regency.

Introduction

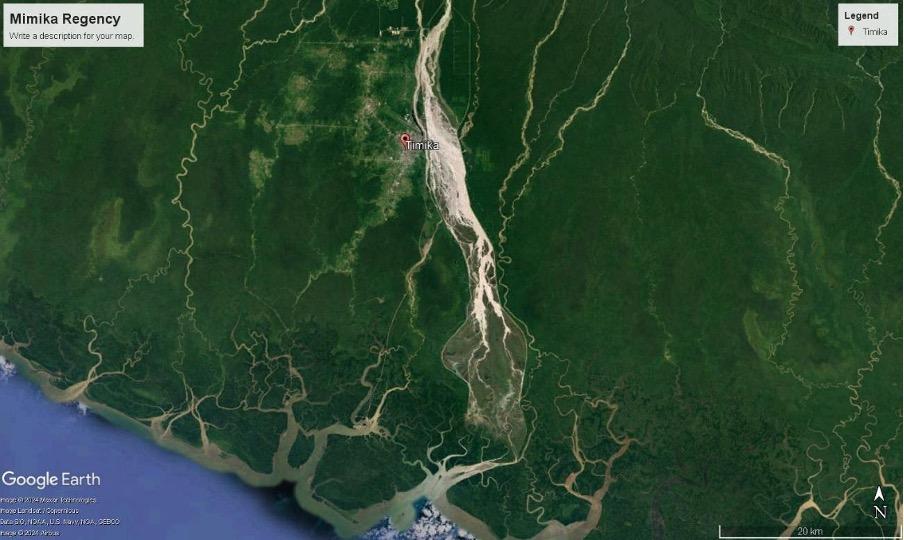

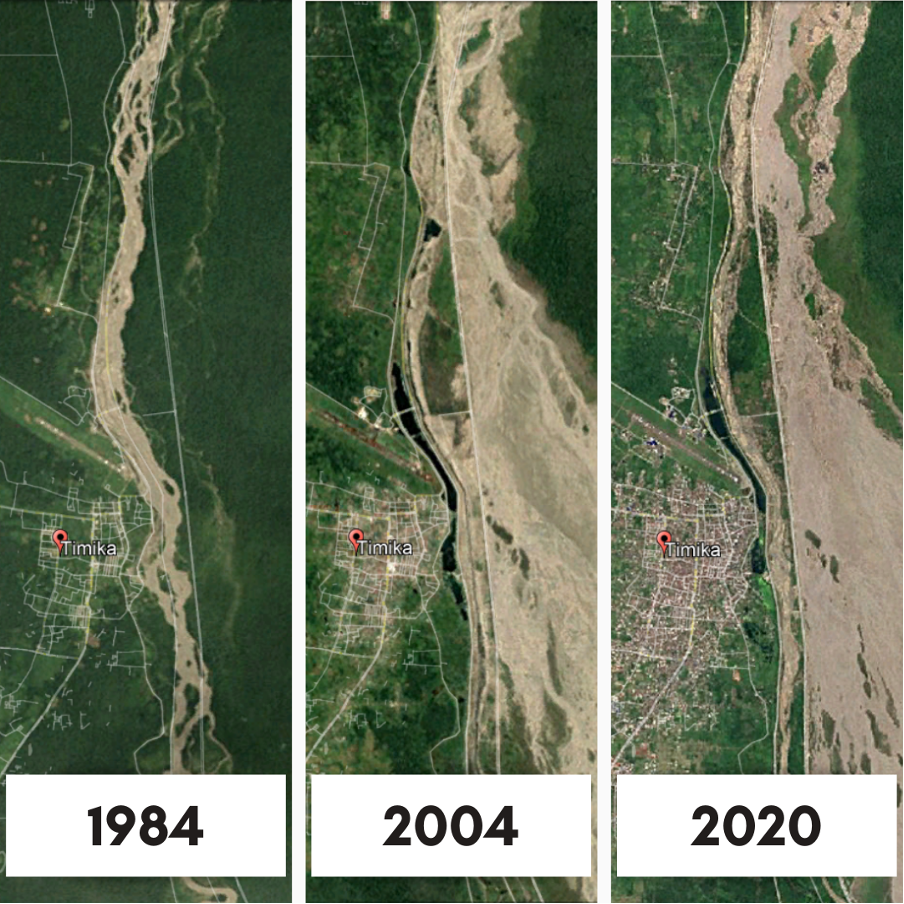

On May 1, 2024, I took a screenshot of a Google Earth satellite image centering on Timika City. To the right of the city, there is a striking light beige area: the mud sediment in the Aghawagon River and Ajkwa River with tailings from PT Freeport Indonesia. The river, due to the massive amount of tailings, has grown since 1974 and has now become wider than Timika City itself. This is not an isolated phenomenon: tailings are widespread and cause sedimentation along vast coastal stretches of Mimika Regency. But what are tailings?

Tailings are waste from the mining industry, gold, copper, silver, or other minerals, resulting from the physical processing of a mill's activities (Masloman, 2009). Tailings waste is created as a by-product and appears in the form of sludge. When ore is crushed and mixed with reagents in a flotation cell, minerals containing copper and gold are separated from rock particles that do not hold any economic value. The resulting concentrate makes up only 3% of the ore processed; the rest is waste sand or tailings. Tailings from gold mining contain several hazardous toxic materials, such as arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), mercury (Hg), cyanide (Cn), and others. These metals are heavy metals that are included in the scientific category of hazardous and toxic materials. These high-sulfur minerals are a potential source for the emergence of acid mine water.

Strategic Issues

Based on the World Population Review in 2024, Indonesia holds the 6th position as a mineral-producing country, with 683.9 million tons of production per year. Indonesia's main mining products are coal, bauxite, gold, tin concentrate, copper concentrate, and nickel ore (Produksi Barang Tambang Mineral, 2024). With its enormous potential, the mining sector contributes to non-tax state revenue. This abundance of mineral resources in Indonesia attracts mining companies from all over the world, such as Freeport and Exxon Mobil Corporation and Chevron Pacific from America, Shell from the Netherlands, BP from England, Petronas from Malaysia, and others who want to operate and invest.

One of the largest companies in the world that mines and processes gold, copper, and silver concentrates is PT Freeport Indonesia. It was founded in 1967 and currently still has an operating permit until 2041. It is a subsidiary of the American company Freeport-McMoRan. PT Freeport Indonesia operates in the highlands of Tembagapura, Mimika Regency, Central Papua, Indonesia. While this enterprise has a positive impact on the country's economic development and provides many jobs, it has a massively negative impact on the environment: large amounts of mining waste and tailings pollute the waters and soil, causing ecosystem damage and endangering human health.

In a document issued by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry in 2019, it is recorded that from 1974 to 2018, PT Freeport Indonesia channeled tailing waste through the Aghawagon River and the Ajkwa River in Mimika Regency. This waste is then placed in the Modified Ajkwa Deposition Area (ModADA), covering an area of 230 square kilometers to avoid tailings overflowing into the Arafuru Sea (Djati Witjaksono Hadi, 2019). This deposit area is a part of the river basin and is an engineered system, managed for the deposition and control of tailings. In one day, more than 200,000 tons of tailings are dumped into the river that flows into the coastal area.

Based on data released by the NGO Wahana Lingkungan Hidup (WALHI — Indonesian Forum for Environment) and the Environment Management Performance Program of PT Freeport Indonesia, PT Freeport Indonesia has dumped tailings classified as hazardous and toxic waste of B3 waste under Government Regulation Number 101 of 2014 "Concerning Management of Hazardous and Toxic Waste of B3 Waste (Hazardous and toxic materials) into the Ajkwa River (Astuti, 2018). These tailings have spread and now reach the coast of the Arafura Sea. The amount of tailings PT Freeport releases into the Ajkwa River exceeds the total suspended solid (TSS) quality standards permitted by Indonesian law. PT Freeport Indonesia's tailings have also polluted the waters at the mouth of the Ajkwa River, contaminated many living creatures, and threatened the waters with large amounts of acid mine water.

PT Freeport Indonesia only recognizes Mimika's customary rights to two tribes, namely the Kamoro tribe, who live in coastal areas, and the Amungme tribe, who live in mountainous regions. Due to the environmental damage that occurred from PT Freeport Indonesia's tailings deposited in the river, the Kamoro tribe was severely affected. The pollution has damaged the waters, which are sources of livelihood for this group of people who are specialized in fishing.

Previously the rivers around the coastal area of Mimika Regency were clean, but around the 1990s, the river water became unsuitable for consumption. The Kamoro people who live on the coast rely on rainwater for their daily needs. They were even relocated to Timika City by the Mimika Regency Government and PT Freeport Indonesia in 1981 due to the impact of tailings; some returned because, after more than 30 years of living in the new settlement, their lives were still far from prosperous. Kamoro people’s lives revolve around water. But as rivers become too contaminated, canoes become oblivious, and sago is slowly being eroded. The younger generation no longer learns how to make traditional long-oared boats, as they simply have no use for them anymore. Hunting and sago staking (processing the flesh of the sago trunk to make sago flour sediment) have also become impossible, as plants and invertebrates living in mangrove areas absorb heavy metals from tailings sediment.

The Impacts

PT Freeport Indonesia’s tailings waste not only poses a threat to the environment but also has substantial negative impacts on the community and the water system as a whole. There are only a few silver linings with a small number of positive consequences.

The negative impacts of dumping tailings into the rivers and sea are apparent in the suffering ecosystem. The mud waste from mining processing thrown into rivers causes sedimentation and makes the rivers shallower, polluting them. This results in the death of fish and trees surrounding the rivers. The local communities are losing their residences and livelihoods in the form of fish and sago, which are contaminated by tailings waste. The surrounding community is affected by several diseases and the water crisis. In addition, the tailings waste is a source of income for illegal miners, who pan for gold from the remaining mining mud despite the dangerous risks involved. The government wants to end the illegal activity because it is suspected that using mercury triggers environmental damage, the impact of which is borne by the locals.

The positive impact of PT Freeport's waste dumping, however counterintuitive this may sound, can be seen in agriculture. The reclaimed and revegetated land can be used for growing crops, developing livestock, and conducting research to develop tailings waste as raw material for building infrastructure, roads, bridges, and drainage channels, which are included in PT Freeport Indonesia’s program. The economic sector benefits from the expanding job market this large enterprise has created.

Challenges

Data regarding the impact of environmental damage on society is still very limited due to company intervention, which prevents this data from being published and accessible to the public. The company even appears to have influence over the researchers' NGO, WALHI. The Indonesian government and PT Freeport Indonesia themselves seem to turn a blind eye to the environmental damage that is occurring. The Indonesian government needs to put pressure on PT Freeport Indonesia regarding their tailings dumping and refrain from determining policies. It is high time the government prioritized the environment to safeguard both people and nature to keep the entire ecosystem, which is crucial to the country’s well-being, intact.

Recommendation

Considering the devastating impact of tailings on humans and the environment, stakeholders, especially the government authorities at national and regional levels, should take their role as the primary policy-makers seriously and prioritize human and environmental security. The government must be able to invite various parties, such as academics and NGOs, to collect data, research, review, and evaluate various impacts caused by tailings in rivers. The government should regulate the private sector, particularly companies that operate to manage tailings waste safely and implement environmentally friendly technologies that mitigate the impact of gold mining. Effective and sustainable management of gold mining waste is essential to prevent environmental pollution.

Acknowledgments

This blog post has been written in the context of discussions in the LDE PortCityFutures research community. It reflects the evolving thoughts of the authors and expresses the discussions between researchers on the socio-economic, spatial, and cultural questions surrounding port city relationships. This blog was edited by the PortCityFutures editorial team: Eliane Schmid and Yi Kwan Chan. Special thanks to Carola Hein for her valuable comments.

References

Astuti, A. D. (2018). Implikasi Kebijakan Indonesia dalam Menangani. Journal of International Relations, 4(3), 547-555.

Djati Witjaksono Hadi, K. B. (2019, January 9). Siaran Pers Masalah Lingkungan PT Freeport Indonesia Sudah Ada Roadmap Penyelesaiannya. Retrieved from Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan Pejabat Pengelola Informasi dan Dokumentasi: https://ppid.menlhk.go.id/siaran_pers/browse/1732

Produksi Barang Tambang Mineral, 2021-2022. (2024, January 11). Badan Pusat Statistik. https://www.bps.go.id/id/statistics-table/2/NTA4IzI=/produksi-barang-tambang-mineral.html

Iikmj. (2024, November 7). Dampak Penambangan Emas terhadap Lingkungan: Ancaman Terhadap Alam dan Manusia. suaramedia.net. https://suaramedia.net/2024/11/07/dampak-penambangan-emas-terhadap-lingkungan/.

Masloman, H. R. (2009). Pemanfaatan Limbah Tambang untuk Bahan Konstruksi. Ekoton, 9 (1), 69-73.

Masrikail, M. Z. (2021, February 27). Morowali di Tengah Ancaman Limbah Tailing. Kamputo.com. https://kamputo.com/morowali-di-tengah-ancaman-limbah-tailing/

Saturi, S. (2013, July 25). Laporan Greenpeace: Freeport Ancam Kelestarian Laut Indonesia. Mongabay Indonesia. https://www.mongabay.co.id/2013/07/25/laporan-greenpeace-freeport-ancam-kelestarian-laut-indonesia/

Septyanto Galan Prakoso, F. A. (2023). The importance of securitization in addressing the environmental issue: Case on Freeport's Tailing Waste. Sustinere: Journal of Environment and Sustainability, 7 (2), 122-133.

Sucahyo, N. (2023, February 1). Limbah Tailing Freeport Rusak Lingkungan, Hancurkan Kehidupan. VOA. https://www.voaindonesia.com/a/limbah-tailing-freeport-rusak-lingkungan-hancurkan-kehidupan-/6943257.html

Sukmalalana, Y. R. (2023). Upaya Penanganan Kerusakan Lingkungan. Pusat Kajian Akuntabilitas. https://berkas.dpr.go.id/pa3kn/analisis-tematik-akuntabilitas/public-file/analisis-ringkas-cepat-public-121.pdf

World Population Review. (2024). Mineral Production by Country 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/mineral-production-by-country